ML-10: Gradient Descent Optimization

Learning Objectives

- Understand gradient descent intuition

- Choose appropriate learning rates

- Compare batch GD vs SGD

- Implement gradient descent from scratch

Theory

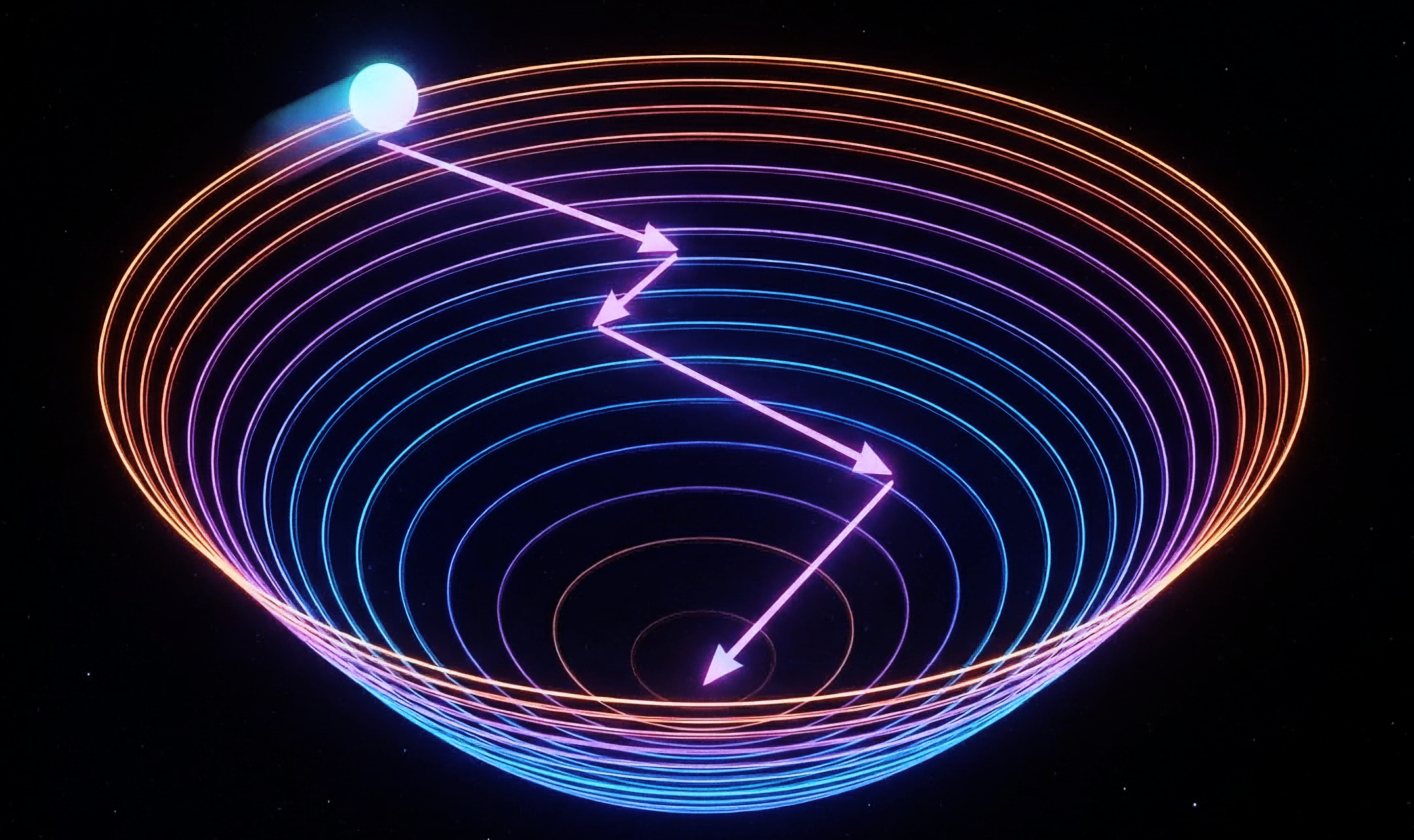

The Core Idea: Finding the Bottom of a Valley

Gradient descent is the workhorse algorithm behind training most machine learning models. The goal is simple: find the parameters that minimize a loss function.

Imagine standing on a hilly landscape in thick fog. The goal is to reach the lowest point (minimum loss), but visibility is limited to just the immediate surroundings. The strategy? Feel the slope under your feet and step downhill. Repeat until flat ground is reached.

This is exactly what gradient descent does mathematically:

- Calculate the slope (gradient) at the current position

- Take a step in the direction of steepest descent

- Repeat until convergence

The Optimization Problem

Given a loss function $J(w)$ that measures how “wrong” the model is, the goal is to find the optimal weights:

$$w^* = \arg\min_w J(w)$$

For most ML problems, $J(w)$ is a complex function of many parameters. Finding the exact minimum analytically is often impossible. Gradient descent provides an iterative numerical solution.

The Gradient: Which Way is Downhill?

The gradient $\nabla J(w)$ is a vector that points in the direction of steepest ascent — the direction where the function increases fastest.

For a function of multiple variables $J(w_1, w_2, …, w_n)$:

$$\nabla J(w) = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial J}{\partial w_1} \ \frac{\partial J}{\partial w_2} \ \vdots \ \frac{\partial J}{\partial w_n} \end{bmatrix}$$

Key insight: To minimize the function, move in the opposite direction of the gradient — the direction of steepest descent.

The Update Rule

The gradient descent update is elegantly simple:

$$w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta \nabla J(w_t)$$

Where:

- $w_t$ = current parameter values

- $\eta$ = learning rate (step size)

- $\nabla J(w_t)$ = gradient at current position

- $w_{t+1}$ = new parameter values

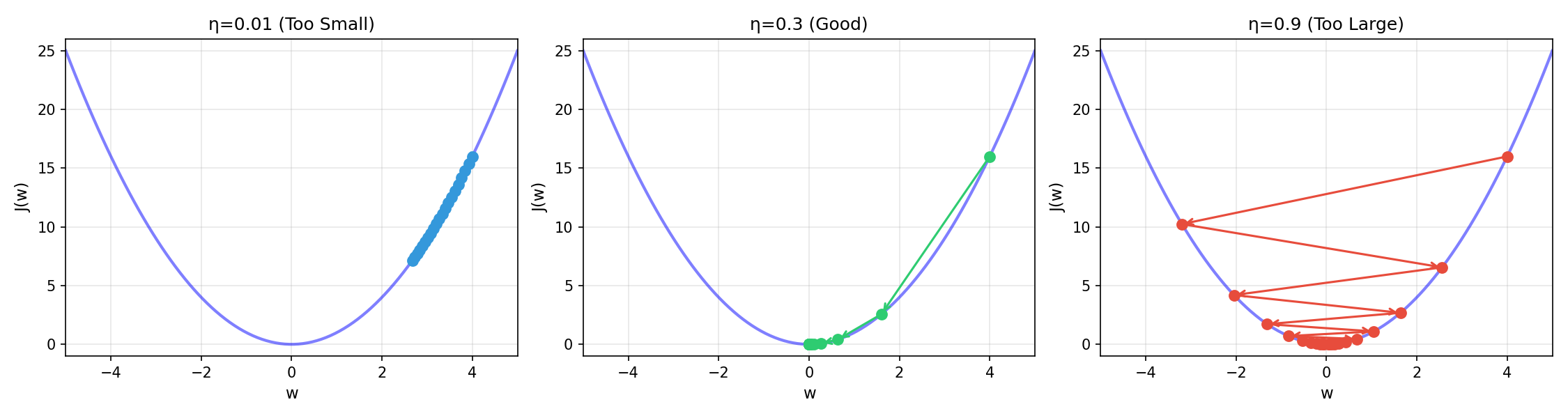

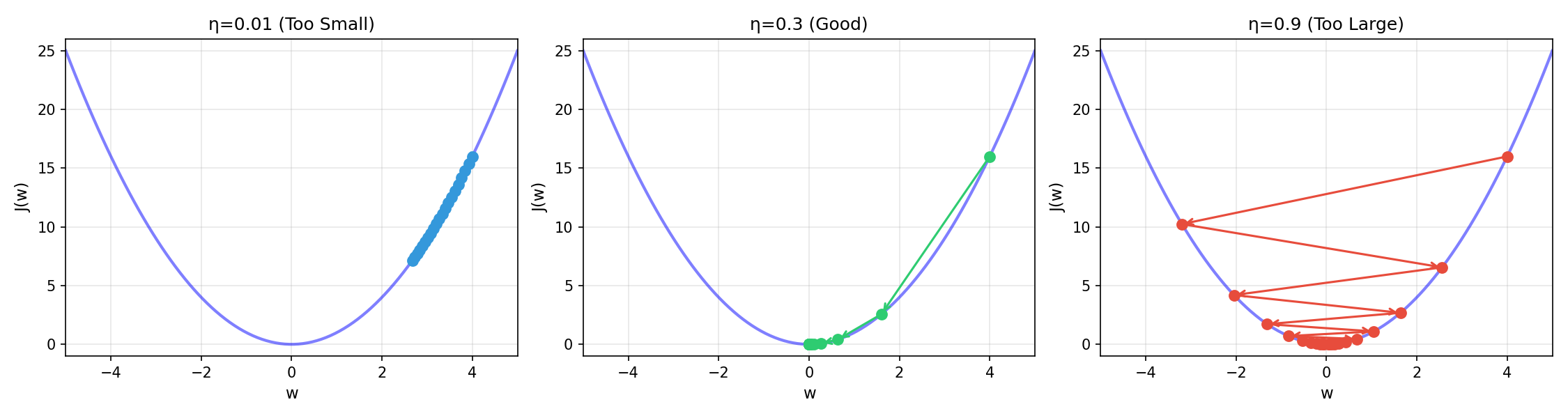

Understanding the Learning Rate

The learning rate $\eta$ controls how big each step is. This single hyperparameter dramatically affects training behavior:

| Learning Rate | Behavior | Visualization |

|---|---|---|

| Too small ($\eta = 0.001$) | Tiny steps, very slow convergence, may get stuck in local minima | Many small steps |

| Too large ($\eta = 0.9$) | Overshoots the minimum, oscillates wildly, may diverge | Jumping back and forth |

| Just right ($\eta = 0.1$) | Steady progress toward minimum, good balance of speed and stability | Smooth convergence |

Practical guidelines for choosing $\eta$:

- Start with common values: 0.01, 0.001, or 0.0001

- If loss decreases too slowly → increase $\eta$

- If loss oscillates or increases → decrease $\eta$

- Consider learning rate schedules that reduce $\eta$ over time

Convergence: When to Stop?

Gradient descent continues until one of these stopping criteria is met:

| Criterion | Description | Typical Value |

|---|---|---|

| Max iterations | Fixed number of updates | 1000-10000 |

| Loss threshold | Stop when loss is small enough | $J(w) < 10^{-6}$ |

| Gradient norm | Stop when gradient is near zero | $|\nabla J| < 10^{-6}$ |

| No improvement | Stop when loss stops decreasing | ΔJ < ε for N iterations |

Batch Gradient Descent vs. Stochastic Gradient Descent

The standard gradient descent formula uses all training samples to compute the gradient:

$$\nabla J(w) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \nabla L(w; x_i, y_i)$$

This is called Batch Gradient Descent (BGD). It’s accurate but slow for large datasets.

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) uses only one random sample per update:

$$\nabla J(w) \approx \nabla L(w; x_i, y_i)$$

Mini-batch GD is the compromise — use a small batch of samples (typically 32-256):

$$\nabla J(w) \approx \frac{1}{B} \sum_{i=1}^{B} \nabla L(w; x_i, y_i)$$

| Method | Samples per Update | Update Speed | Gradient Quality | Memory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch GD | All N | Slow | Accurate | High |

| SGD | 1 | Very Fast | Very Noisy | Low |

| Mini-batch | B (32-256) | Fast | Good Estimate | Moderate |

Why does SGD work despite noisy gradients?

The noise in SGD gradients acts as implicit regularization — it helps escape local minima and can lead to better generalization. The key insight is that while each individual update may be inaccurate, the average direction over many updates still points toward the minimum.

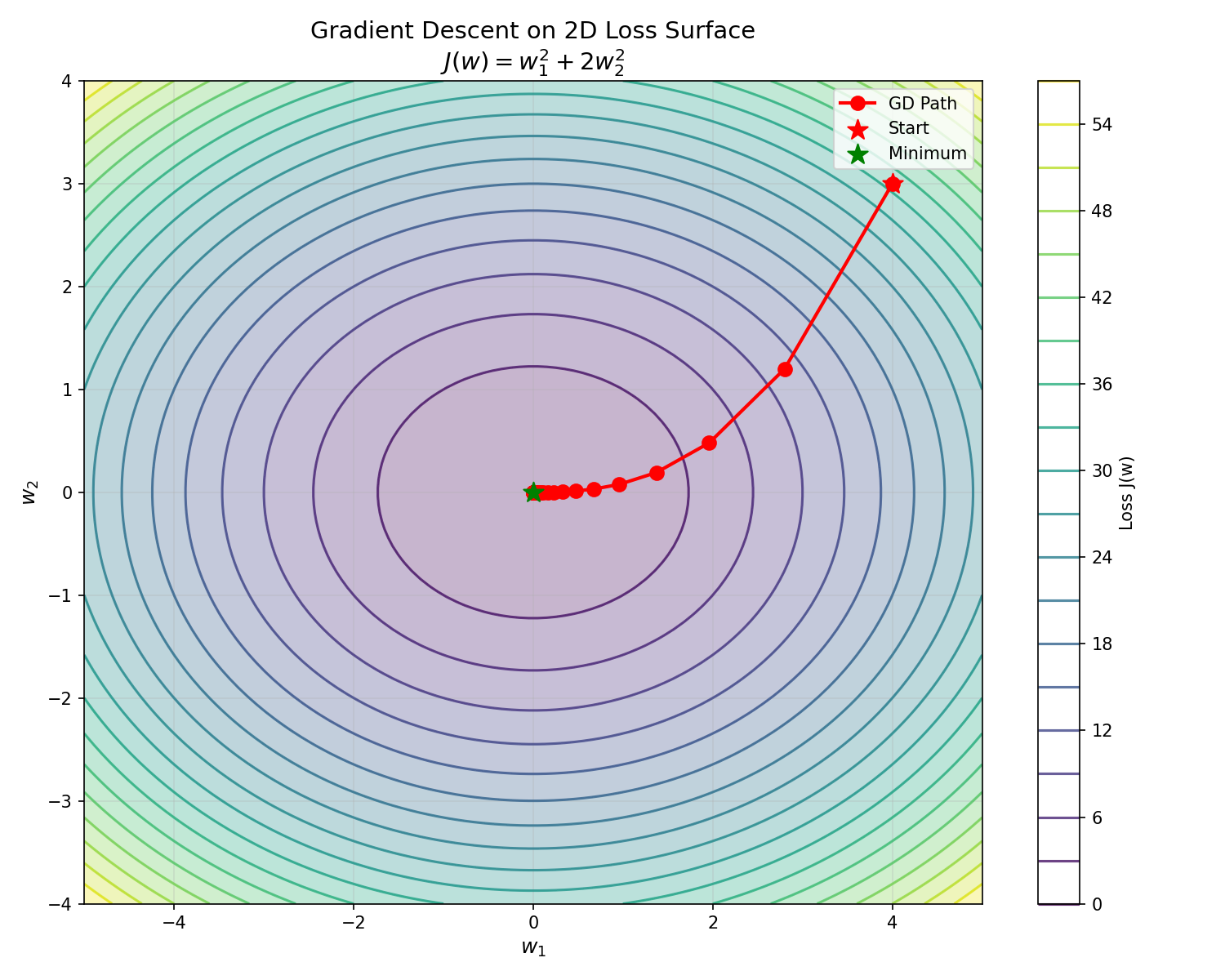

The Loss Landscape Perspective

Visualizing the loss function as a landscape helps build intuition:

- Convex functions (like linear/logistic regression loss): One global minimum, gradient descent always converges

- Non-convex functions (like neural networks): Multiple local minima and saddle points, convergence depends on initialization and learning rate

Code Practice

This section demonstrates gradient descent through interactive visualizations and practical implementations.

Learning Rate Comparison

The following code visualizes how different learning rates affect convergence:

🐍 Python

| |

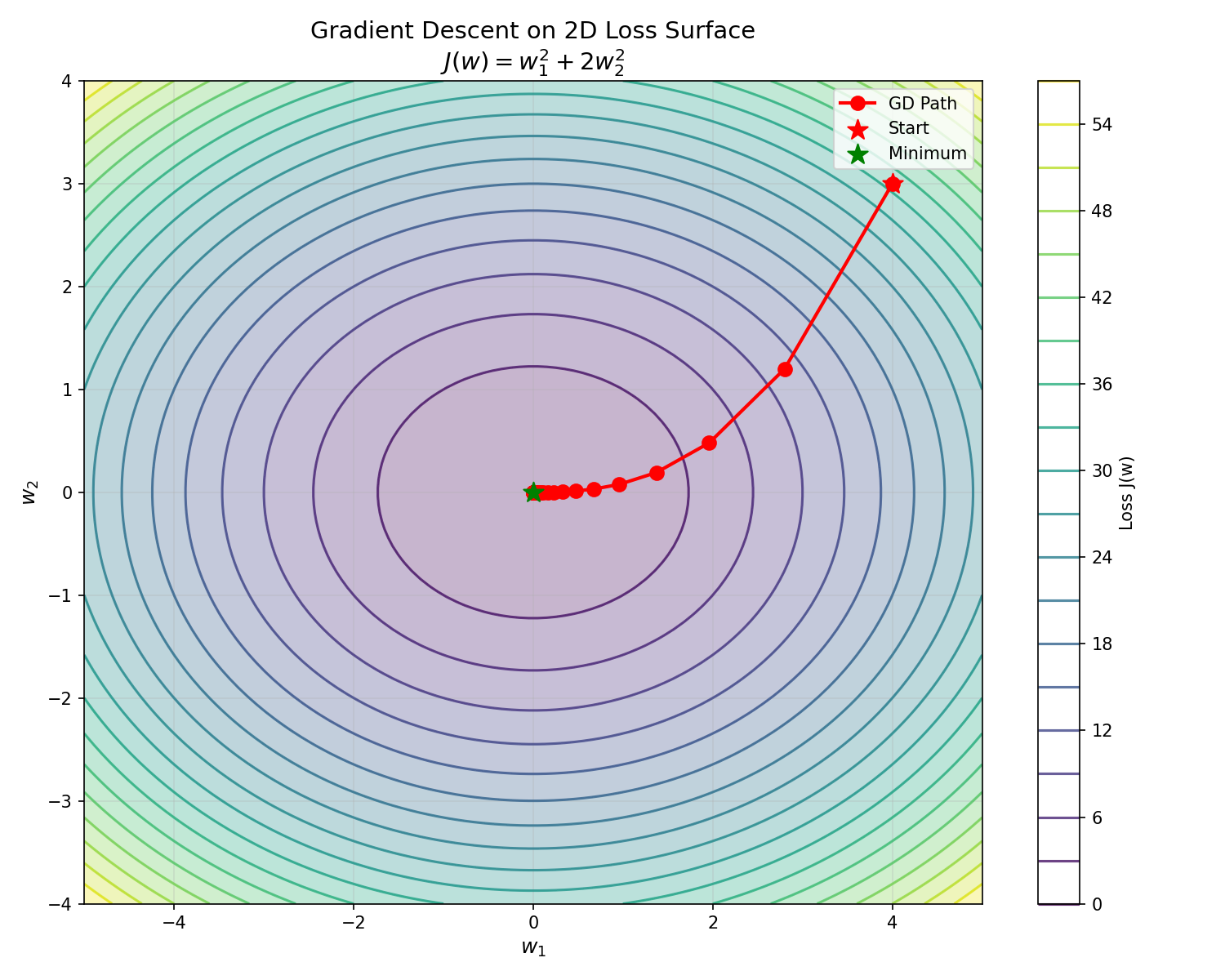

2D Contour Plot: Gradient Descent Path

Visualizing gradient descent on a 2D loss surface provides deeper intuition:

🐍 Python

| |

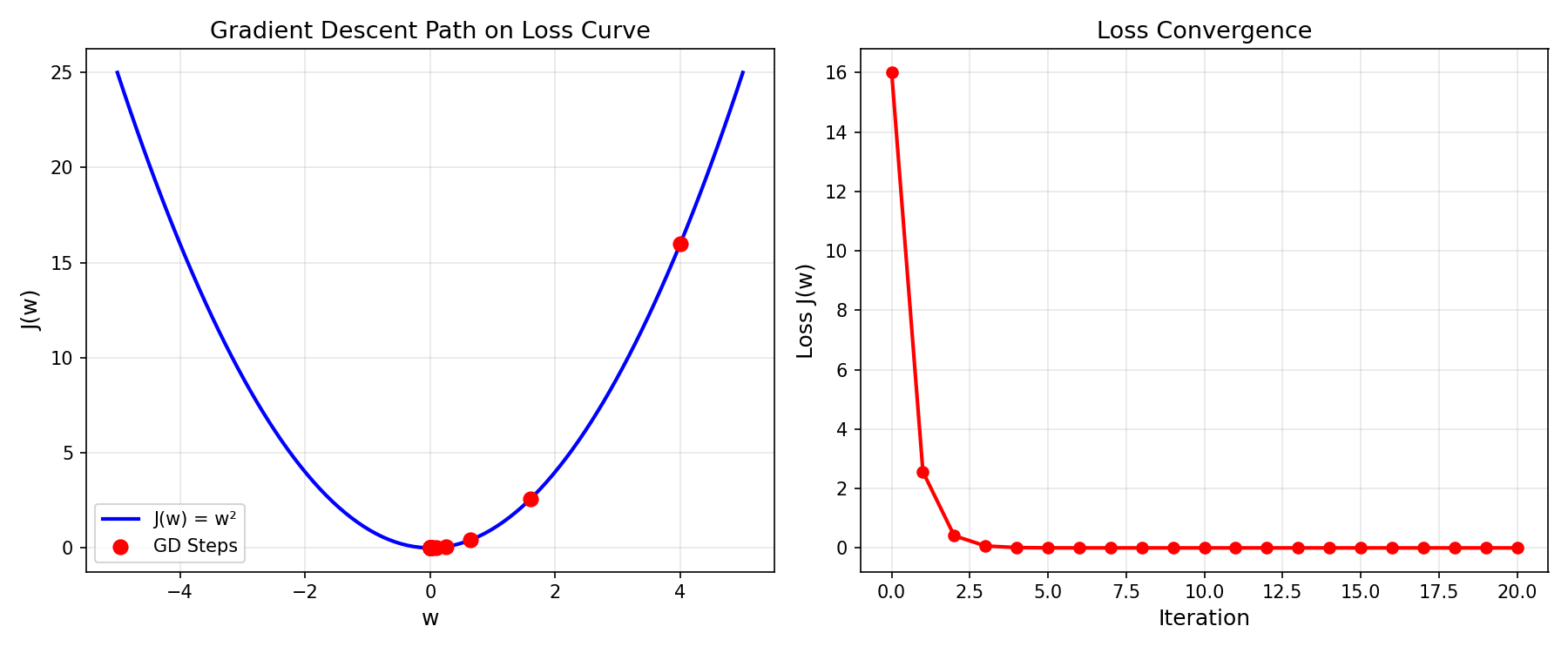

Gradient Descent on a Simple Parabola

🐍 Python

| |

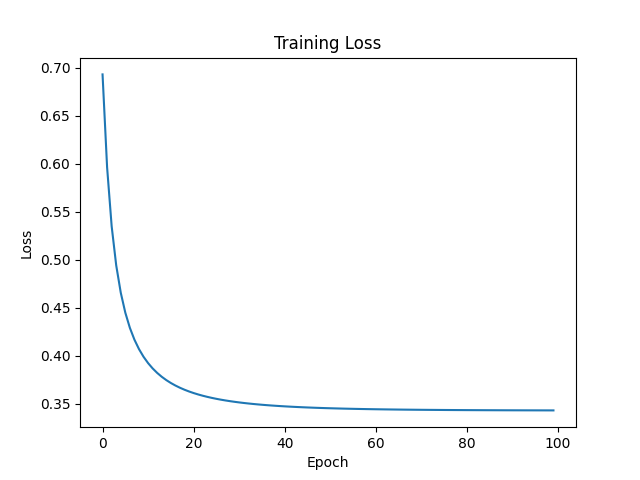

Logistic Regression with Gradient Descent

🐍 Python

| |

SGD Implementation

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

| |

Comparing GD vs SGD

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

Deep Dive

This section addresses common questions and introduces advanced optimization techniques.

Q1: How to choose the right learning rate?

Finding the optimal learning rate is one of the most important hyperparameter decisions. Practical approaches include:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Grid search | Try values like 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 and compare loss curves |

| Learning rate finder | Gradually increase $\eta$ during one epoch and plot loss vs. $\eta$; choose the value before loss explodes |

| Rule of thumb | Start with 0.01 for SGD, 0.001 for Adam |

Q2: When to use SGD vs. batch GD?

| Scenario | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Small dataset (< 10K samples) | Batch GD or quasi-Newton methods (L-BFGS) |

| Large dataset (> 100K samples) | SGD or Mini-batch with momentum |

| Need fast iteration | SGD with small batches |

| Need high precision | Batch GD or L-BFGS |

| Deep learning | Mini-batch + Adam (most common) |

Q3: What mini-batch size should be used?

| Batch Size | Trade-offs |

|---|---|

| 1 (pure SGD) | Maximum noise, fastest per-iteration, may not converge |

| 32-64 | Good balance, common default for deep learning |

| 128-256 | More stable gradients, efficient GPU utilization |

| 512+ | Very stable but may generalize worse, needs larger learning rate |

Note: Powers of 2 (32, 64, 128, 256) are GPU-friendly due to memory alignment.

Advanced Optimizers

While basic gradient descent works, modern ML uses adaptive optimizers that automatically adjust learning rates:

Momentum

Standard GD can oscillate in ravines (narrow valleys). Momentum adds “velocity” to smooth out oscillations:

$$v_t = \gamma v_{t-1} + \eta \nabla J(w_t)$$ $$w_{t+1} = w_t - v_t$$

Where $\gamma \approx 0.9$ is the momentum coefficient. This accelerates convergence and dampens oscillations.

RMSprop

RMSprop adapts learning rates per-parameter based on recent gradient magnitudes:

$$E[g^2]_t = \gamma E[g^2]_{t-1} + (1-\gamma) g_t^2$$ $$w_{t+1} = w_t - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{E[g^2]_t + \epsilon}} g_t$$

This helps with sparse features and prevents the learning rate from becoming too small.

Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation)

Adam combines the best of Momentum and RMSprop — it’s the most popular optimizer for deep learning:

$$m_t = \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1-\beta_1) g_t \quad \text{(first moment)}$$ $$v_t = \beta_2 v_{t-1} + (1-\beta_2) g_t^2 \quad \text{(second moment)}$$ $$w_{t+1} = w_t - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{\hat{v}_t} + \epsilon} \hat{m}_t$$

Default hyperparameters: $\beta_1 = 0.9$, $\beta_2 = 0.999$, $\epsilon = 10^{-8}$

| Optimizer | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| SGD | Simple, good generalization | Slow, sensitive to learning rate |

| SGD + Momentum | Faster, handles ravines | Extra hyperparameter |

| RMSprop | Adaptive, good for RNNs | May not converge in some cases |

| Adam | Fast, robust, works out-of-the-box | May generalize worse than SGD |

| |

Learning Rate Schedules

Keeping $\eta$ constant throughout training may not be optimal. Learning rate schedules reduce $\eta$ over time:

| Schedule | Formula | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Step decay | $\eta_t = \eta_0 \cdot \gamma^{\lfloor t/s \rfloor}$ | Simple, common baseline |

| Exponential | $\eta_t = \eta_0 \cdot e^{-kt}$ | Smooth decay |

| Cosine annealing | $\eta_t = \eta_{min} + \frac{1}{2}(\eta_0 - \eta_{min})(1 + \cos(\frac{t\pi}{T}))$ | Popular in deep learning |

| Warmup + decay | Start low, increase, then decay | Large batch training |

Summary

Key Formulas

| Concept | Formula |

|---|---|

| Gradient Descent | $w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta \nabla J(w_t)$ |

| Batch Gradient | $\nabla J = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \nabla L(w; x_i, y_i)$ |

| SGD Gradient | $\nabla J \approx \nabla L(w; x_i, y_i)$ |

| Momentum | $v_t = \gamma v_{t-1} + \eta \nabla J$, $w = w - v$ |

Key Takeaways

- Gradient descent minimizes loss iteratively — no closed-form solution needed

- Learning rate is critical — too small is slow, too large diverges

- SGD trades accuracy for speed — noisy gradients but faster updates

- Mini-batch balances the trade-off — typical sizes: 32-256

- Adaptive optimizers (Adam) often work best — automatically adjust learning rates

- Learning rate schedules improve convergence — reduce $\eta$ over time

Practical Recommendations

| Task | Recommended Setup |

|---|---|

| Linear/Logistic Regression | Batch GD or L-BFGS |

| Deep Learning (CV) | SGD + Momentum + LR schedule |

| Deep Learning (NLP) | Adam with warmup |

| Quick prototyping | Adam with default settings |

References

- Bottou, L. (2010). “Large-Scale Machine Learning with Stochastic Gradient Descent”

- Kingma, D. & Ba, J. (2014). “Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization”

- Ruder, S. (2016). “An Overview of Gradient Descent Optimization Algorithms”

- sklearn SGD Classifier

- PyTorch Optimizers