ML-11: SVM: Hard Margin and Duality

Learning Objectives

- Understand the maximum margin intuition

- Formulate the hard-margin optimization problem

- Identify support vectors

- Grasp the dual problem basics

Theory

What is SVM?

Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a supervised learning algorithm for classification and regression tasks. First introduced by Vapnik and colleagues in the 1990s, SVM remains one of the most powerful and widely-used classifiers in machine learning.

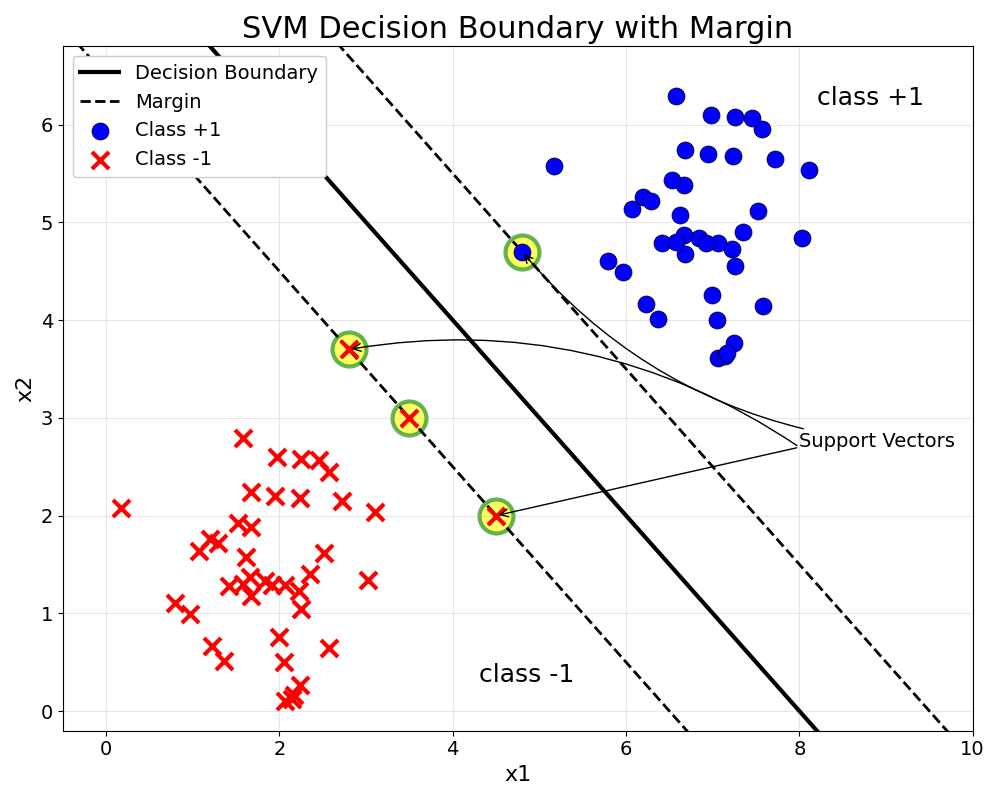

The core idea: find the optimal hyperplane that separates different classes with the maximum margin. Unlike other classifiers that simply find any separating boundary, SVM seeks the boundary that is most robust to new data.

Why Maximize Margin?

When separating two groups of points, infinitely many lines can achieve perfect classification — but which one is best?

Key insight: A classifier with a larger margin is more robust and generalizes better. The margin acts as a “safety buffer” — the wider it is, the higher the confidence that new, unseen points will be classified correctly.

| Margin Size | Robustness | Generalization |

|---|---|---|

| Small | ⚠️ Sensitive to noise | Poor on new data |

| Large | ✅ Robust to perturbations | Better generalization |

A small margin means even tiny perturbations in data could cause misclassification. A large margin provides robustness against noise and improves generalization to new data.

Hyperplane Geometry

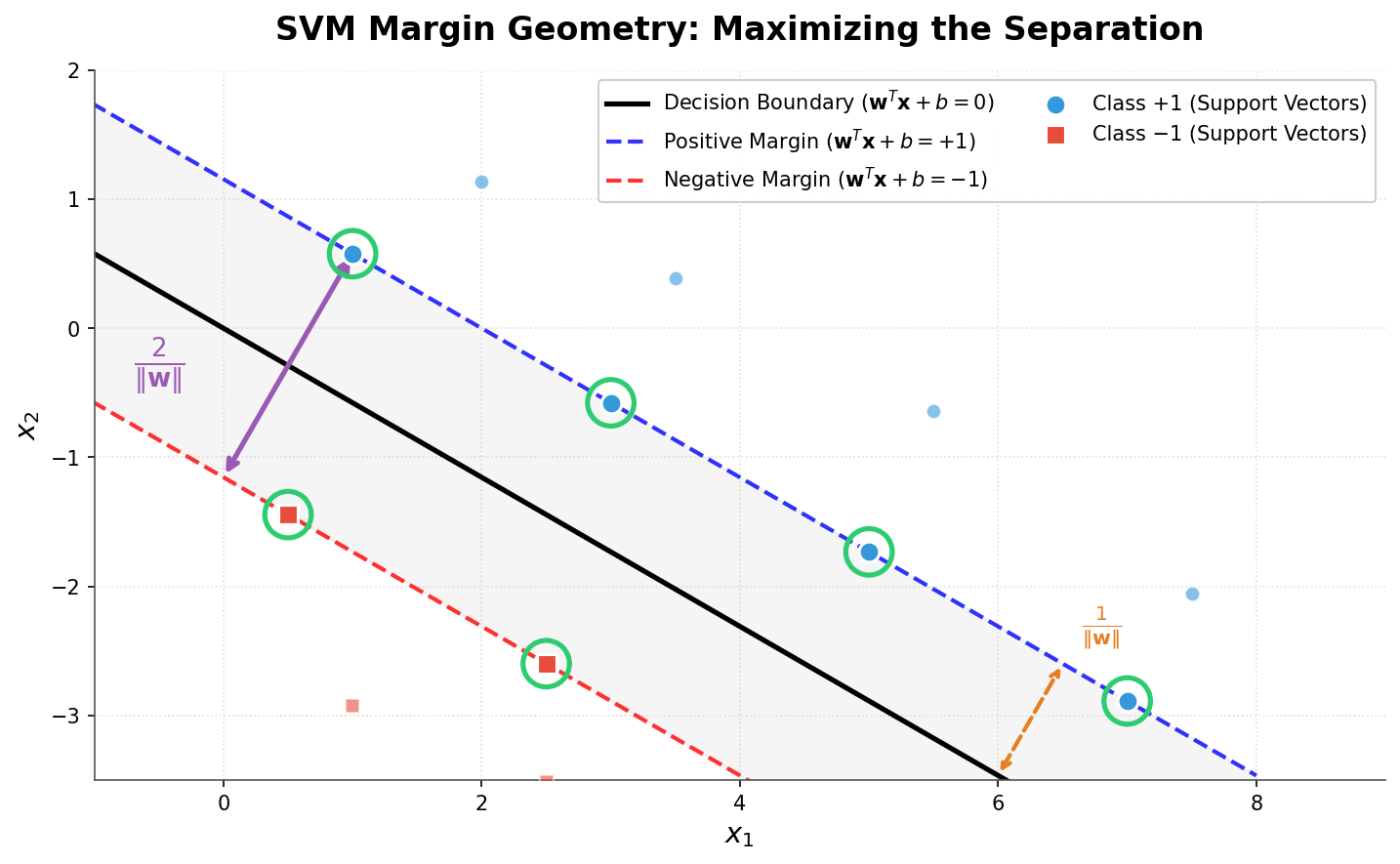

A hyperplane in $\mathbb{R}^n$ is defined by:

$$w^T x + b = 0$$

where:

- $w \in \mathbb{R}^n$ is the normal vector (perpendicular to the hyperplane)

- $b \in \mathbb{R}$ is the bias (shifts the hyperplane from the origin)

Distance from a Point to Hyperplane

For any point $x_0$, the signed distance to the hyperplane is:

$$\text{distance} = \frac{w^T x_0 + b}{|w|}$$

For a correctly classified point with label $y_i \in {-1, +1}$:

$$\text{functional margin} = y_i(w^T x_i + b)$$

$$\text{geometric margin} = \frac{y_i(w^T x_i + b)}{|w|}$$

The geometric margin is the actual Euclidean distance, invariant to scaling of $w$ and $b$.

From Margin to Optimization

Goal: Find the hyperplane that maximizes the minimum geometric margin.

Step 1: Define the Margin

The margin of the classifier is the distance to the nearest point:

$$\gamma = \min_i \frac{y_i(w^T x_i + b)}{|w|}$$

Step 2: Normalize the Constraints

Since scaling $w$ and $b$ produces the same hyperplane, this freedom can be fixed by requiring that for the closest points:

$$y_i(w^T x_i + b) = 1 \quad \text{(for support vectors)}$$

This means all other points satisfy:

$$y_i(w^T x_i + b) \geq 1$$

With this normalization, the geometric margin of the closest points becomes:

$$\gamma = \frac{1}{|w|}$$

Step 3: Formulate the Optimization Problem

Maximize margin → Maximize $\dfrac{1}{|w|}$ → Minimize $|w|$ → Minimize $\dfrac{1}{2}|w|^2$

Why $\dfrac{1}{2}|w|^2$ instead of $|w|$?

- Squaring removes the square root (easier derivatives)

- The $\dfrac{1}{2}$ factor simplifies the gradient (derivative of $\dfrac{1}{2}x^2$ is simply $x$)

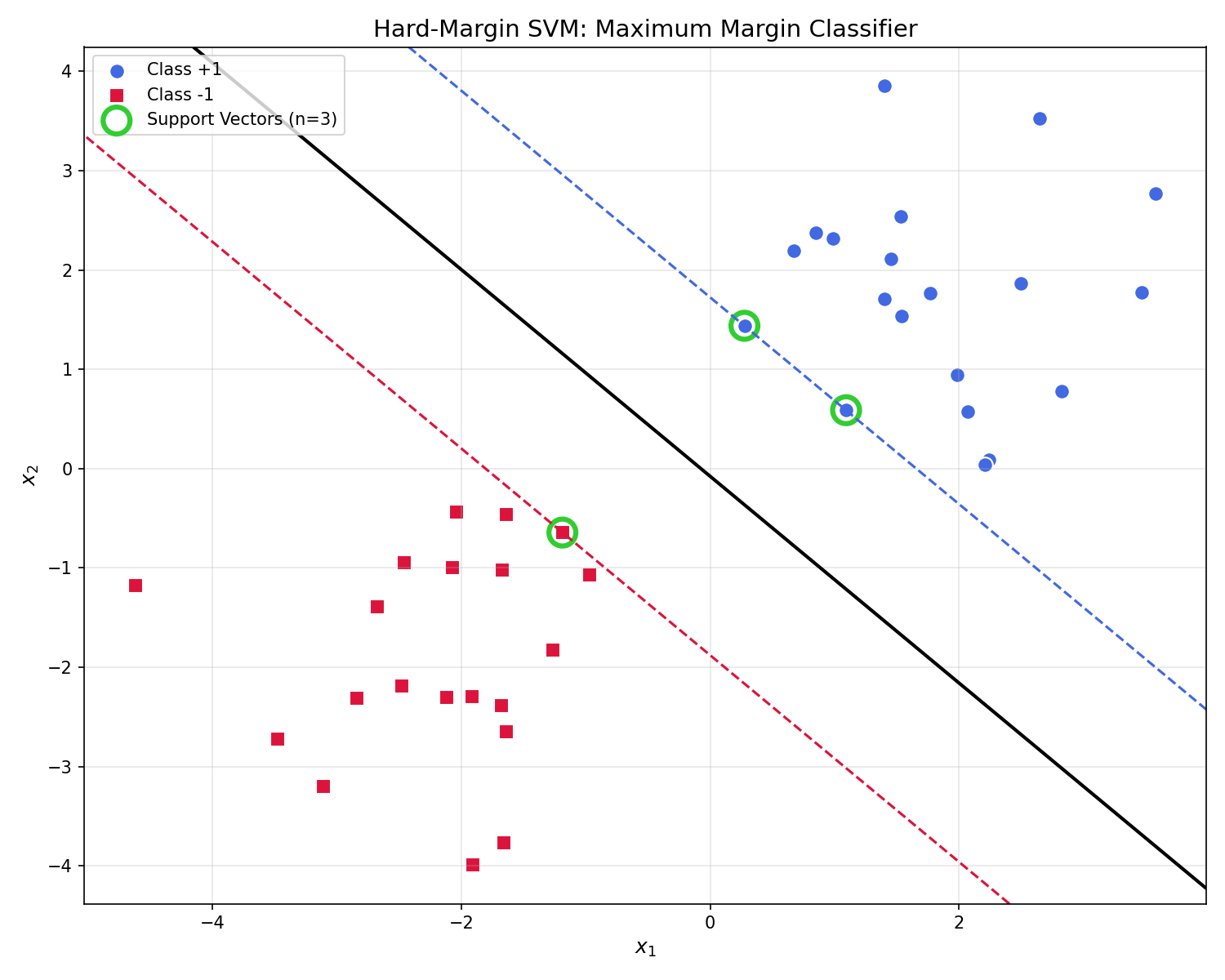

The Hard-Margin SVM Primal Problem:

$$\boxed{\min_{w,b} \frac{1}{2}|w|^2 \quad \text{s.t.} \quad y_i(w^T x_i + b) \geq 1, ; \forall i = 1, \ldots, N}$$

Support Vectors

Support vectors are the critical data points that lie exactly on the margin boundary:

$$y_i(w^T x_i + b) = 1$$

Key properties:

- They are the closest points to the decision boundary

- They fully determine the hyperplane — remove other points and the solution doesn’t change

- Typically only a small subset of training points are support vectors

Lagrangian and KKT Conditions

To solve the constrained optimization problem, Lagrange multipliers are introduced.

The Lagrangian

Introduce multipliers $\alpha_i \geq 0$ for each constraint:

$$\mathcal{L}(w, b, \alpha) = \frac{1}{2}|w|^2 - \sum_{i=1}^{N} \alpha_i \left[ y_i(w^T x_i + b) - 1 \right]$$

The primal problem becomes:

$$\min_{w,b} \max_{\alpha \geq 0} \mathcal{L}(w, b, \alpha)$$

KKT Conditions (Intuitive View)

The Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions are necessary and sufficient for optimality:

| Condition | Meaning |

|---|---|

| $\nabla_w \mathcal{L} = 0$ | Stationary point w.r.t. $w$ |

| $\nabla_b \mathcal{L} = 0$ | Stationary point w.r.t. $b$ |

| $\alpha_i \geq 0$ | Dual feasibility |

| $y_i(w^T x_i + b) \geq 1$ | Primal feasibility |

| $\alpha_i [y_i(w^T x_i + b) - 1] = 0$ | Complementary slackness |

Deriving the Dual Problem

The KKT conditions provide a path to solve for $w$ and $b$.

Step 1: Differentiate and Set to Zero

$$\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial w} = w - \sum_{i=1}^{N} \alpha_i y_i x_i = 0 \quad \Rightarrow \quad \boxed{w = \sum_{i=1}^{N} \alpha_i y_i x_i}$$

$$\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial b} = -\sum_{i=1}^{N} \alpha_i y_i = 0 \quad \Rightarrow \quad \boxed{\sum_{i=1}^{N} \alpha_i y_i = 0}$$

Step 2: Substitute Back into Lagrangian

Substituting $w = \sum_i \alpha_i y_i x_i$ into $\mathcal{L}$:

$$\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} \left| \sum_i \alpha_i y_i x_i \right|^2 - \sum_i \alpha_i y_i \left( \sum_j \alpha_j y_j x_j \right)^T x_i - b\sum_i \alpha_i y_i + \sum_i \alpha_i$$

Since $\sum_i \alpha_i y_i = 0$, the $b$ term vanishes. After simplification:

$$\mathcal{L} = \sum_i \alpha_i - \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i,j} \alpha_i \alpha_j y_i y_j x_i^T x_j$$

Step 3: The Dual Problem

The Hard-Margin SVM Dual Problem:

$$\boxed{\begin{aligned} \max_\alpha \quad & \sum_{i=1}^{N} \alpha_i - \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i,j} \alpha_i \alpha_j y_i y_j (x_i^T x_j) \\ \text{s.t.} \quad & \alpha_i \geq 0, ; \forall i \\ & \sum_{i=1}^{N} \alpha_i y_i = 0 \end{aligned}}$$

Why the Dual Matters

The dual formulation has several crucial advantages:

| Advantage | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Depends only on dot products | The objective involves only $x_i^T x_j$, not individual features |

| Enables the kernel trick | Replace $x_i^T x_j$ with $K(x_i, x_j)$ to handle nonlinear boundaries |

| Efficiency for high-dimensional data | When $n \gg N$ (features » samples), dual is more efficient |

| Sparse solution | Most $\alpha_i = 0$; only support vectors have $\alpha_i > 0$ |

Code Practice

The following examples demonstrate Hard-Margin SVM implementation and visualization of the optimal separating hyperplane.

Hard-Margin SVM Visualization

This example generates linearly separable data and trains an SVM with a very large C value (regularization parameter) to simulate hard-margin behavior. A large C means the model strongly penalizes any misclassification, effectively enforcing hard constraints.

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

The solid black line is the decision boundary ($w^Tx + b = 0$). The dashed lines show the margin boundaries where $w^Tx + b = \pm 1$. Points circled in green are the support vectors — notice how they lie exactly on the margin boundaries.

Examining Support Vectors

The following code inspects the learned model parameters and verifies the margin calculation.

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

| |

Using sklearn SVM in Practice

The following example presents a more realistic scenario with train/test split and accuracy evaluation.

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

Deep Dive

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does maximizing the margin improve generalization?

This connects to statistical learning theory. Intuitively:

- Robustness: A larger margin means small perturbations (noise) in the data are less likely to cause misclassification

- VC Dimension: Larger margins correspond to lower VC dimension, which bounds generalization error

- Structural Risk Minimization: SVM balances empirical error (training accuracy) with model complexity (margin width)

Consider: if a decision boundary barely squeezes between two classes, any new data point slightly different from training data might fall on the wrong side. A wide margin provides a “buffer zone.”

Q2: How do support vectors fully determine the decision boundary?

From the dual solution:

$$w = \sum_{i=1}^{N} \alpha_i y_i x_i$$

Due to complementary slackness, $\alpha_i > 0$ only for support vectors. This means:

$$w = \sum_{i \in SV} \alpha_i y_i x_i$$

To find $b$, any support vector $x_s$ can be used: $$b = y_s - w^T x_s$$

Implication: All non-support-vector training points can be discarded after training — predictions rely only on SVs!

Q3: What if data is not linearly separable?

Hard-margin SVM will fail (no feasible solution exists). Two options are available:

| Solution | Description |

|---|---|

| Soft-Margin SVM | Allow some misclassifications with slack variables |

| Kernel SVM | Map data to higher dimensions where it becomes separable |

If using hard-margin SVM with C=1e10 on non-separable data, the solver may:

- Take very long to converge

- Return unstable solutions

- Fail entirely

Q4: SVM vs. Logistic Regression — When to use which?

| Aspect | SVM | Logistic Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Maximize margin | Minimize log-loss |

| Output | Decision boundary only | Class probabilities |

| Sparsity | Uses only SVs | Uses all training points |

| Outlier sensitivity | More robust (hard margin ignores interior points) | Sensitive to outliers |

| Best for | Clear margin between classes | When probabilities are needed |

Rule of thumb:

- Need probabilities? → Logistic Regression

- Clean separation, want robustness? → SVM

- High-dimensional data (text, genomics)? → SVM often works well

Computational Complexity

| Operation | Primal | Dual |

|---|---|---|

| Training | $O(N \cdot d^3)$ | $O(N^2 \cdot d) \text{ to } O(N^3)$ |

| Prediction | $O(d)$ | $O(\lvert SV \rvert \cdot d)$ |

Where $N$ = number of samples, $d$ = number of features, $|SV|$ = number of support vectors.

Practical implications:

- High-dimensional data ($d \gg N$): Dual is preferred

- Many samples ($N \gg d$): Primal may be faster

- Sparse SVs: Prediction is very fast

Practical Tips

StandardScaler or MinMaxScaler before training.Check linear separability first: Plot your data. If classes clearly overlap, go straight to soft-margin or kernel SVM.

Monitor support vector count:

- Too few SVs → Model might be too simple

- Too many SVs (approaching $N$) → Data may not be separable, or C is too low

Start with large C, then reduce: Begin with

C=1000(near hard-margin), then decrease if overfitting.Use

sklearn’s dual parameter: ForLinearSVC, setdual='auto'to let sklearn choose the optimal formulation.

Common Pitfalls

| Pitfall | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unscaled features | Poor accuracy, slow convergence | Use StandardScaler |

| Non-separable data with hard margin | Solver fails/hangs | Reduce C or use soft margin |

| Too many features | Overfitting | Use regularization (smaller C) |

| Imbalanced classes | Bias toward majority class | Use class_weight='balanced' |

Summary

| Concept | Key Points |

|---|---|

| Maximum Margin | Find hyperplane with largest gap |

| Objective | $\min \dfrac{1}{2}|w|^2$ |

| Constraint | $y_i(w^T x_i + b) \geq 1$ |

| Support Vectors | Points on margin boundary |

| Dual | Only depends on $x_i^T x_j$ (enables kernels!) |

References

- Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. (1995). “Support-Vector Networks”

- sklearn SVM Documentation

- Boyd, S. “Convex Optimization” - Chapter 5