ML-06: Linear Regression

Learning Objectives

- Understand regression vs classification

- Derive the least squares solution

- Implement linear regression from scratch

- Extend to multiple features

Theory

Regression vs Classification

| Task | Output Type | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Classification | Discrete labels | Spam or not spam |

| Regression | Continuous values | House price prediction |

Classification answers “which category?” while regression answers “how much?”

Linear Model

$$\hat{y} = w_0 + w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + \cdots = \boldsymbol{w}^T \boldsymbol{x}$$

Where $\boldsymbol{x} = (1, x_1, x_2, \ldots)^T$ includes the bias term (intercept).

Breaking it down:

- $w_0$ is the intercept (baseline prediction when all features are 0)

- $w_1, w_2, \ldots$ are weights that determine how much each feature contributes

- Each weight tells the model: “for every 1-unit increase in this feature, change the prediction by this amount”

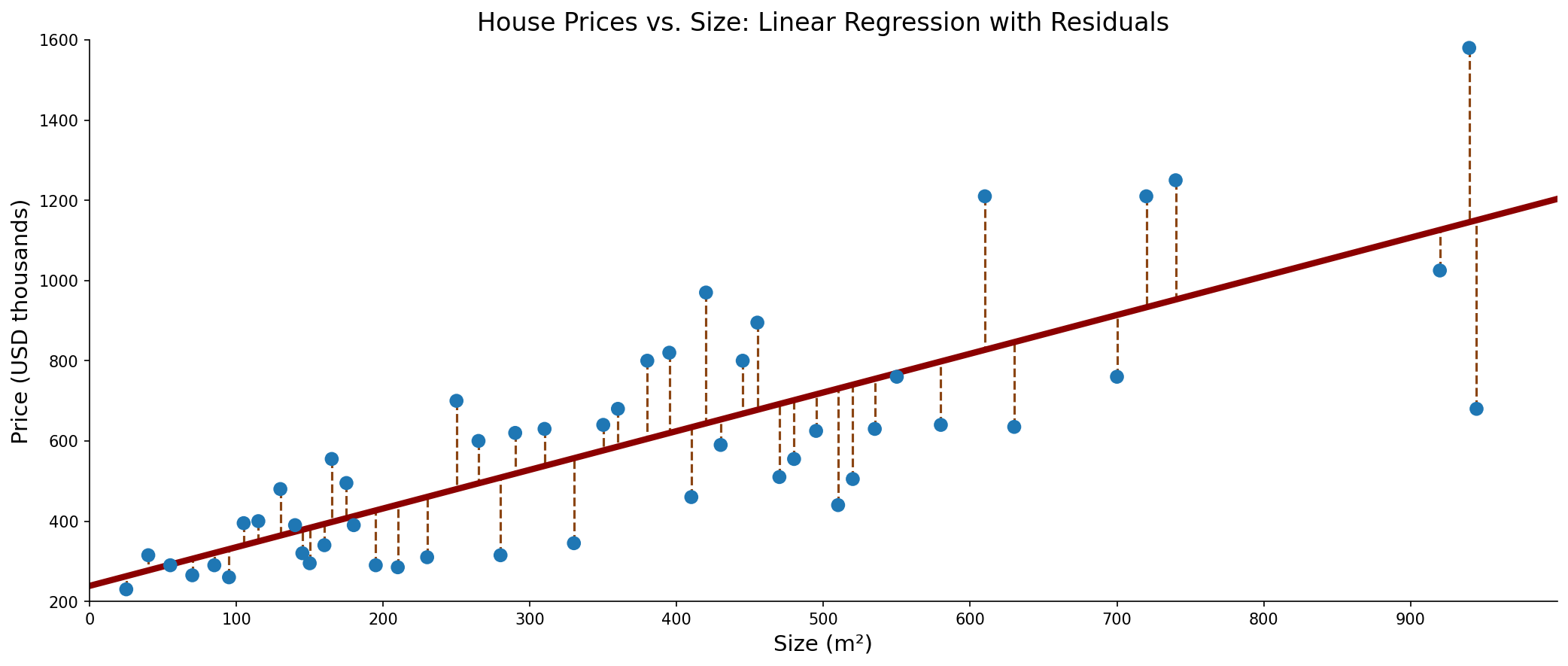

Why Squared Error?

The goal is to find the “best” line through data points. What makes a line optimal? Consider these error metrics:

| Error Metric | Formula | Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of errors | $\sum (y_i - \hat{y}_i)$ | ❌ Positive and negative errors cancel out |

| Sum of absolute errors | $\sum \vert y_i - \hat{y}_i \vert$ | ✓ Works, but not differentiable at 0 |

| Sum of squared errors | $\sum (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2$ | ✓ Differentiable, penalizes large errors more |

Key insight: Squared error is preferred because:

- It’s always positive (no cancellation)

- It’s smooth and differentiable (enables calculus-based optimization)

- It penalizes large errors heavily (one big error is worse than several small ones)

Least Squares Objective

Minimize the sum of squared errors:

$$J(\boldsymbol{w}) = \sum_{i=1}^{N} (y_i - \boldsymbol{w}^T \boldsymbol{x}_i)^2 = |\boldsymbol{y} - X\boldsymbol{w}|^2$$

In matrix form, where $X$ is the design matrix (each row is a sample, each column is a feature):

- $\boldsymbol{y}$ = vector of true values $(y_1, y_2, \ldots, y_N)^T$

- $X\boldsymbol{w}$ = vector of predictions

- $|\cdot|^2$ = squared Euclidean norm

Deriving the Closed-Form Solution

The optimal weights can be derived step by step.

Step 1: Expand the objective function

$$J(\boldsymbol{w}) = (\boldsymbol{y} - X\boldsymbol{w})^T(\boldsymbol{y} - X\boldsymbol{w})$$

Expanding the product:

$$J(\boldsymbol{w}) = \boldsymbol{y}^T\boldsymbol{y} - 2\boldsymbol{w}^T X^T \boldsymbol{y} + \boldsymbol{w}^T X^T X \boldsymbol{w}$$

Step 2: Take the gradient with respect to $\boldsymbol{w}$

Using matrix calculus rules:

- $\frac{\partial}{\partial \boldsymbol{w}}(\boldsymbol{w}^T \boldsymbol{a}) = \boldsymbol{a}$

- $\frac{\partial}{\partial \boldsymbol{w}}(\boldsymbol{w}^T A \boldsymbol{w}) = 2A\boldsymbol{w}$ (when $A$ is symmetric)

$$\nabla_w J = -2X^T\boldsymbol{y} + 2X^T X\boldsymbol{w}$$

Step 3: Set gradient to zero and solve

$$-2X^T\boldsymbol{y} + 2X^T X\boldsymbol{w}^* = 0$$

$$X^T X \boldsymbol{w}^* = X^T \boldsymbol{y}$$

$$\boldsymbol{w}^* = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T \boldsymbol{y}$$

This is the normal equation — a direct, closed-form solution for linear regression.

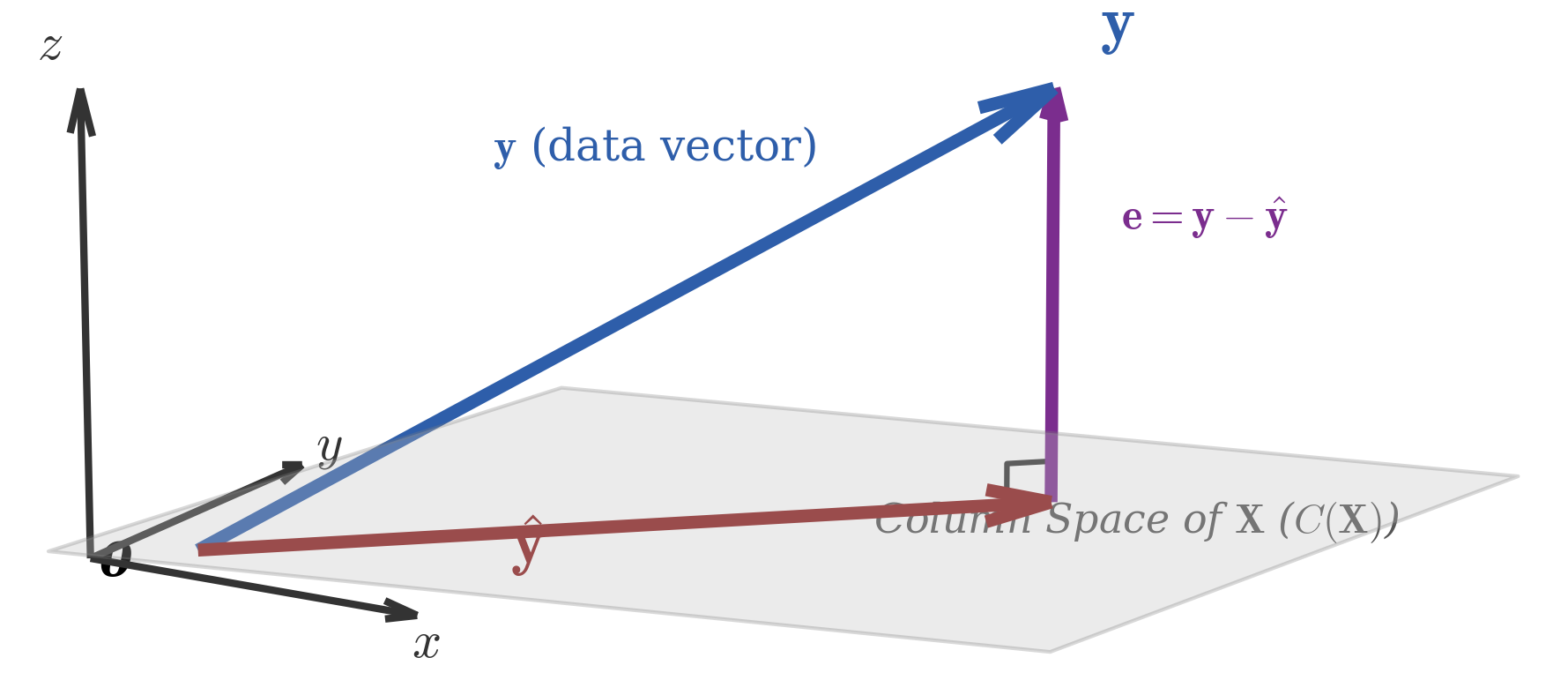

Geometric Interpretation

The prediction $\hat{\boldsymbol{y}} = X\boldsymbol{w}$ is the projection of $\boldsymbol{y}$ onto the column space of $X$.

Why projection? The intuition:

- The column space of $X$ contains all possible predictions the model can make

- The true $\boldsymbol{y}$ might not be in this space (data is rarely perfectly linear)

- The closest point in this space to $\boldsymbol{y}$ is its orthogonal projection

- “Closest” in Euclidean distance = minimizing squared error!

The orthogonality condition: The residual vector $(\boldsymbol{y} - \hat{\boldsymbol{y}})$ is perpendicular to every column of $X$:

$$X^T(\boldsymbol{y} - X\boldsymbol{w}) = 0$$

This is exactly the normal equation rearranged—geometry and calculus yield the same answer.

Understanding R² Score

The coefficient of determination ($R^2$) measures how well the model explains the variance in the data:

$$R^2 = 1 - \frac{SS_{res}}{SS_{tot}} = 1 - \frac{\sum(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{\sum(y_i - \bar{y})^2}$$

Where:

- $SS_{res}$ = Residual sum of squares (unexplained variance)

- $SS_{tot}$ = Total sum of squares (total variance)

- $\bar{y}$ = mean of $y$

Interpreting R²:

| R² Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | Perfect fit — model explains all variance |

| 0.8 | Good — 80% of variance explained |

| 0.5 | Moderate — half the variance explained |

| 0.0 | Model is no better than predicting the mean |

| < 0 | Model is worse than predicting the mean |

Code Practice

From Scratch Implementation

🐍 Python

| |

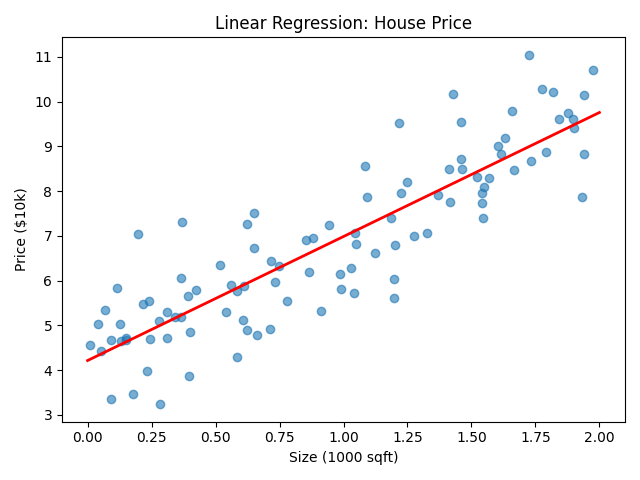

Example: House Price

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

Multiple Linear Regression

🐍 Python

| |

Output:

Deep Dive

Q1: When does the normal equation fail?

The normal equation $\boldsymbol{w}^* = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T \boldsymbol{y}$ requires inverting $X^T X$, which can fail or be problematic in several cases:

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Singular matrix | Features are linearly dependent (e.g., feature_3 = 2 × feature_1) | Remove redundant features or use regularization |

| Near-singular matrix | Features are highly correlated (multicollinearity) | Use Ridge regression (L2 regularization) |

| Large dataset | Matrix inversion is $O(n^3)$, slow for millions of samples | Use gradient descent (iterative, $O(n)$ per step) |

| More features than samples | $X^T X$ is not full rank when $p > n$ | Use regularization or dimensionality reduction |

Practical rule of thumb: Use normal equation for small datasets (< 10,000 samples), gradient descent for large ones.

Q2: What does a negative coefficient mean?

A negative weight indicates an inverse relationship: as that feature increases, the prediction decreases (holding other features constant).

Examples:

- House prices: “years since renovation” → negative (older renovation = lower price)

- Test scores: “hours of distraction” → negative (more distraction = lower score)

- Fuel efficiency: “vehicle weight” → negative (heavier = less efficient)

Q3: Linear regression vs. correlation?

These concepts are related but serve different purposes:

| Aspect | Correlation (r) | Linear Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Measure relationship strength | Predict values |

| Output | Single number (-1 to 1) | Prediction function $\hat{y} = w^T x$ |

| Directionality | Symmetric (r(X,Y) = r(Y,X)) | Asymmetric (X predicts Y) |

| Units | Unitless | Same units as Y |

| Relationship | $R^2 = r^2$ for simple linear regression | — |

Key insight: The correlation coefficient $r$ measures how tightly points cluster around any best-fit line. The relationship $R^2 = r^2$ shows the proportion of variance explained—both convey the same information in different forms.

Q4: How to handle categorical features?

Linear regression works with numbers, so categorical features must be encoded:

| Method | Example | When to use |

|---|---|---|

| One-hot encoding | Color: [Red, Blue, Green] → [1,0,0], [0,1,0], [0,0,1] | Nominal categories (no order) |

| Ordinal encoding | Size: [S, M, L] → [1, 2, 3] | Ordinal categories (with order) |

Summary

| Concept | Formula/Meaning |

|---|---|

| Linear Model | $\hat{y} = \boldsymbol{w}^T \boldsymbol{x}$ |

| Loss Function | $|y - X w|^2$ (squared error) |

| Solution | $w = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T y$ |

| R² Score | Proportion of variance explained |

References

- Bishop, C. “Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning” - Chapter 3

- sklearn Linear Regression Documentation

- Montgomery, D. “Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis”